Vintage: Trailers

The movie trailer is a well-understood advertising form today, but where did it come from? In the 1910s, trailers were shown after the main feature (hence the name) as a way of boring patrons out of the theater to make room for the next showing. The studios and exhibitors were slow to catch on to the fact that, hey, the advertising potential here is tremendous. But by the late 1920s, not only were trailers valuable advertising, they became the bread and butter of third party companies set up to make them.

The first trailer, though it wasn't recognizable by the definition of the term we use today, was shown in 1912 or 1913 (sources differ) for a serial called The Adventures of Kathlyn. This was the first serial with the cliffhanger endings that would soon become standard for serials. Kathlyn is thrown into the lion's den. "Does she escape the lion's pit? See next week's thrilling chapter!"

Eventually, this idea evolved into showing a preview of the next movie the theater had on its schedule. If the theater already had a print of the film (actually it would be unlikely an exhibitor would receive it earlier than the night before the first showing), maybe it would just show the first reel of the film unaltered. Maybe the projectionist would cut the good parts out of the actual print, splice it together into a "trailer," then reassemble the film afterward. More likely, the theater would come up with its own way of advertising the next feature after the current one had ended.

As I said in the beginning of this, part of it was to get patrons out of the theater when a movie ended. Moving pictures were so new and so novel, they'd come in the afternoon and stay all night and enjoy multiple showings of the same program. The idea sounds crazy, but in the 1910s, the novelty of moving pictures hadn't worn off, and it's not like people were overladen with on-demand entertainment choices anyhow. Why, in 1915, most people didn't even have one hundred cable channels. So to make room for later showings, why not take a break, show some stills for next week's shows? Instead of spending the rest of the night in the theater, come back next week for even more fun.

Paramount was quickest to catch on to trailers as a real advertising form. In 1916, they started distributing their own trailers, and in 1919, they set up their own trailer division within the company.

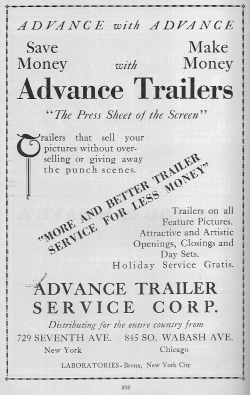

The other studios were slower on the uptake. Trailers were often still seen as a problem for the exhibitor, not the studio, which is consistent with the Ballyhoo posts we've been running here, which are collections of marketing stunts given to exhibitors, not the studios, to advertise their films. (Of course, the line is further blurred when, starting in the late 1920s, studios increasingly own the movie theaters until that practice is finally ruled a monopoly and broken up.)

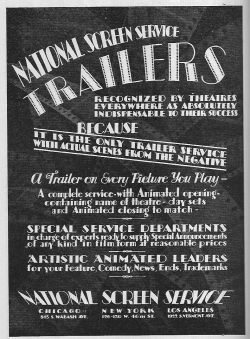

The NSS was so successful, in fact, that in 1940 the major studios signed exclusive contracts with it to produce and distribute advertising materials. This arrangement lasted all the way up to the 1970s, waning from then until the early 1990s. With the advent of the multiplex and the standardization of movie poster sizes, movie advertising became more and more streamlined until finally it became more economical for the studios to take back those responsibilities. Ultimately, Technicolor bought out the NSS in 2000.

But although the NSS is no longer the king of the movie trailer world, it's interesting how movie trailers still generally look the same. Trailer editors find a formula that works, and they stick with it.

And that opens the door to some great parodies now and again. My two favorites: The Comedian and Five Guys In a Limo.

|